Information in English

Key Facts

- 12.500 participating teachers

- Evaluated in 1,943 primary school children and 973 kindergarten children

- 3.379 participating nurseries, kindergartens and schools

- Ca. 200,000 children yearly participate in the program

Program

Inactivity and an unhealthy diet contribute to overweight and obesity among young children. Since these health behaviors develop during early childhood, it’s crucial that health promotion starts at a young age.

The multi-component school- based health promotion program Join the Healthy Boat was developed for children aged 0-10 years and aims at promoting

- daily physical activity

- active, screen-free leisure time

- higher consumption of fruits and vegetables and decreased consumption of sugar-sweetened beverages

- relaxation and mindfulness

Through this program, children learn how to establish behaviours which contribute positively to their overall health and development. The program consists of training sessions and practice proven materials for educational professionals and families, which can be integrated into kindergarten and school curriculum. Join the Healthy Boat has been implemented in schools and kindergartens throughout Baden-Württemberg since 2009 and 2014, respectively.

Development

At the heart of the program is an evidence-based and theory-driven intervention development. It consists of hands-on materials (in German) which were developed by an interdisciplinary team of researchers at the University Hospital of Ulm and an educational advisory board.

Join the Healthy Boat was developed by means of Bartholomew’s Intervention Mapping Approach (Bartholomew et al., 2006). Additionally, the social-cognitive theory by Bandura (Bandura, 2001) and Bronfenbrenner’s ecological framework for human development (Bronfenbrenner, 1979) were applied. RE-AIM was used to structure the evaluation, review and continuous improvement of Join the Healthy Boat, to include modern policy aspects.

Intervention strategy

Join the Healthy Boat applies a teacher-delivery model, whereby caregivers and educators are trained to implement the program directly in their own day care centres and classrooms. These training sessions take place in the form of workshops, which are offered free of charge to all interested teachers and educators living in Baden-Wurttemberg, Germany. Theoretical background knowledge as well as the handling of the materials is taught in the training sessions. The associated support materials are also provided to educators and teachers free of charge.

This inclusive program aims at primary prevention and integrates all children, their peer group and parents in order to involve their entire environment, thus promoting self-motivation. Therefore, aspects such as health inequity and social inequality are tackled and prevented and vulnerable groups such as girls or children with a migration background are included as the program aims for a social and societal change. Using two pirate children, Finn and Fine, as identification figures, the content is conveyed in an engaging, child-friendly way.

Evaluation

Join the Healthy Boat is one of the few successful health promotion programs in Germany that can demonstrate significant intervention effects on different target parameters. The Program was evaluated as part of the “Health Survey” (kindergarten) and “Baden-Württemberg Study” (primary school).

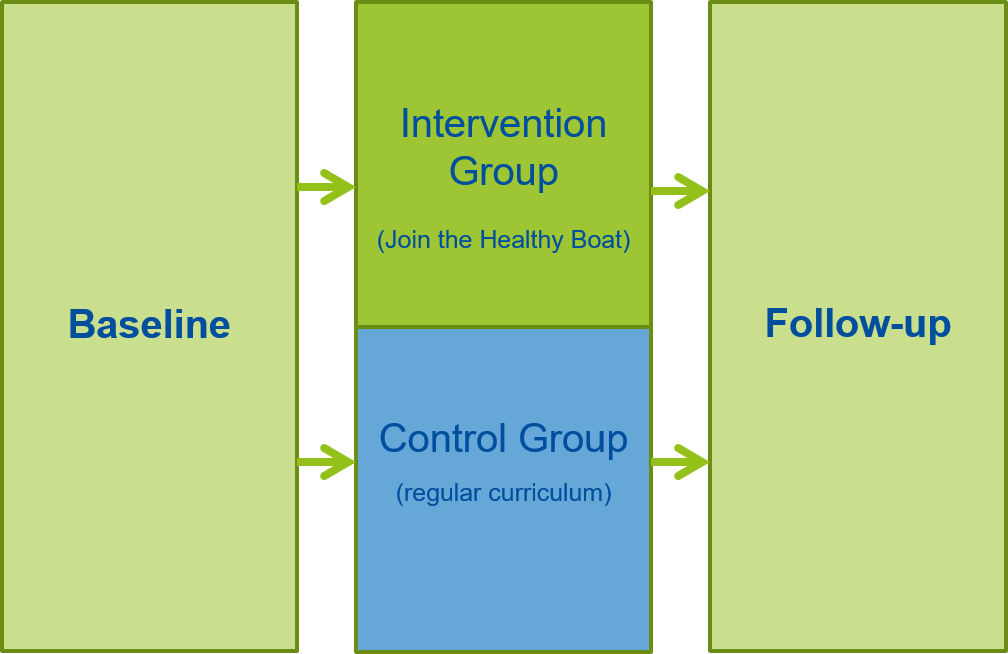

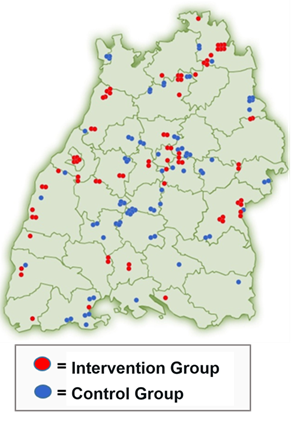

Baden-Württemberg Study

The Baden-Württemberg Study assessed the efficacy of the Join the Healthy Boat Program among primary school children in Baden-Württemberg, Germany. For this study, a prospective, stratified, cluster randomized, longitudinal study design was chosen. Participating primary schools were recruited on a voluntary basis. As part of this study, 91 schools were randomized to receive the Join the Health Boat Program for one year or to the control group (45 in the intervention group, 46 in the control group).

Methods

Efficacy of the intervention was assessed by changes in the following primary outcomes: waist circumference, skinfold thickness, and 6-minute run. The following conditional skills were also measured, as secondary outcomes: standing long jump, sit-ups, push-ups, lateral jumps, and one-legged stand. Flexibility was measured with sit and reach tests. Additional behavioural and environmental changes, which were assessed through parental report, include the following parameters: physical, mental, and emotional health; health-related quality of life (HRQL); behaviour-related cognition; physical activity behaviour; screen media use, nutritional behaviours, self-efficacy, socio-demographic parameter; familial and social history; education; school environment; and health-economic aspects. Further secondary aspects, such as physical activity, inhibition and cognition were assessed objectively.

Parental questionnaires were issued at baseline, and one year later at follow-up, and returned within a six-week time period. Objective measurements took place during a school visit and included thorough assessments of children’s motor skills and body composition (Dreyhaupt et al., 2012).

In total, 1,943 primary school children (7.1 ± 0.6 years) in 157 classes were assessed at baseline. Around 89% of them (1,736 primary school children) were also assessed at follow-up. Parental questionnaires were completed and returned from 1,583 parents (Dreyhaupt et al., 2012).

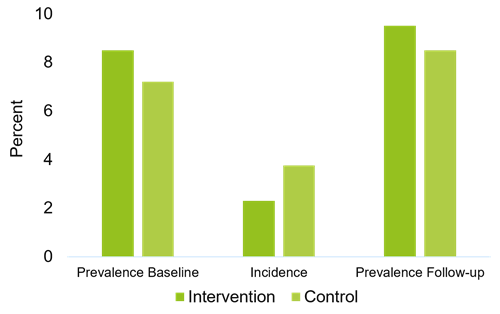

Body composition

In conjunction with age and sex, corresponding weight statuses were determined based on German reference data (Kromeyer-Hauschild et al., 2001). Overall, 91% of the children were of normal weight, 9% were either overweight or obese, and 4% were obese at baseline (Kobel et al., 2014) . Significant changes in weight status were not seen during the intervention.

The number of children who were classified as abdominally obese increased from baseline to follow-up (7.8% to 9.2%, respectively). The odds of developing abdominal obesity in the intervention group were less than half as great as in the control group (Kobel et al., 2019a).

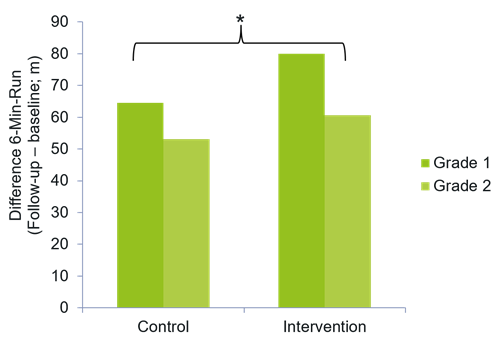

Motor skills

Children in the intervention group saw greater improvements in their endurance capability (measured with a 6-minutes-run) from baseline to follow-up, as children in the control group (70.51 ± 128.62 m; p = 0.046) (Kobel et al., 2019a).

Primary children in the intervention group showed also significant improvements in their conditional skills (described in METHODS) (F (1,1571) = 5.20, p ≤ 0.02), and less decline in their flexibility than those in the control group (F (1,1715) = 6.68, p ≤ 0.01) (Lämmle et al., 2017).

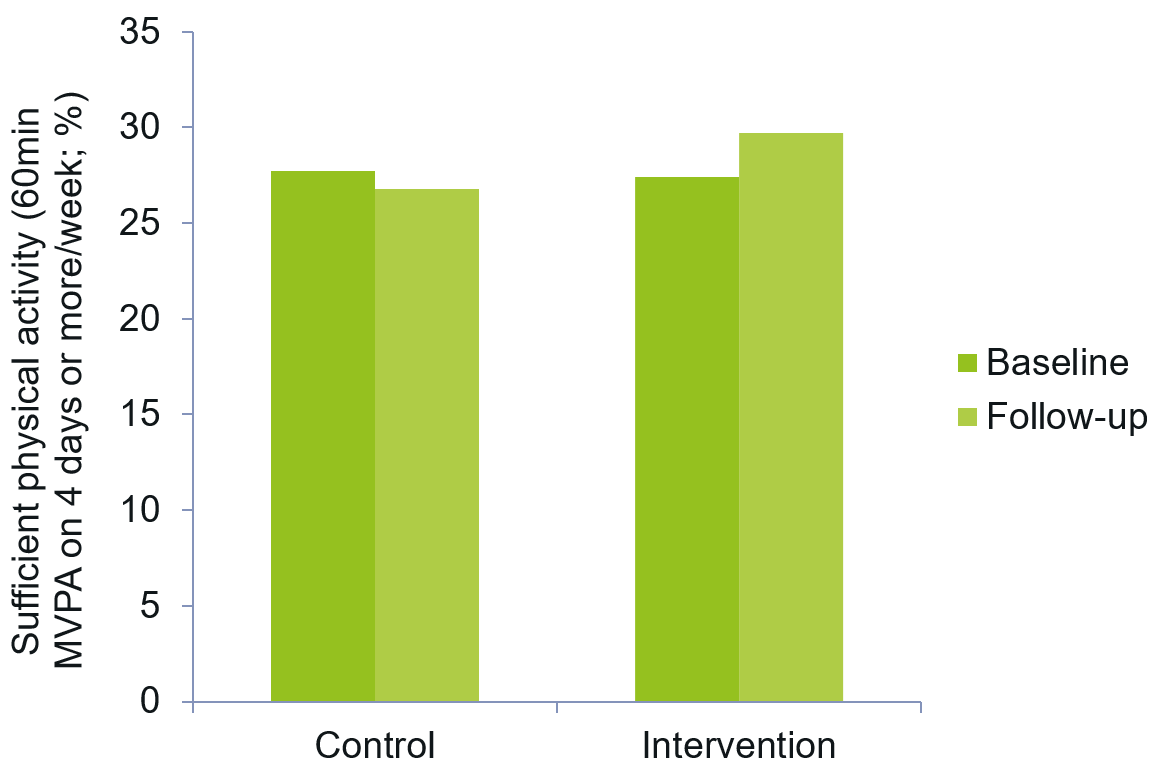

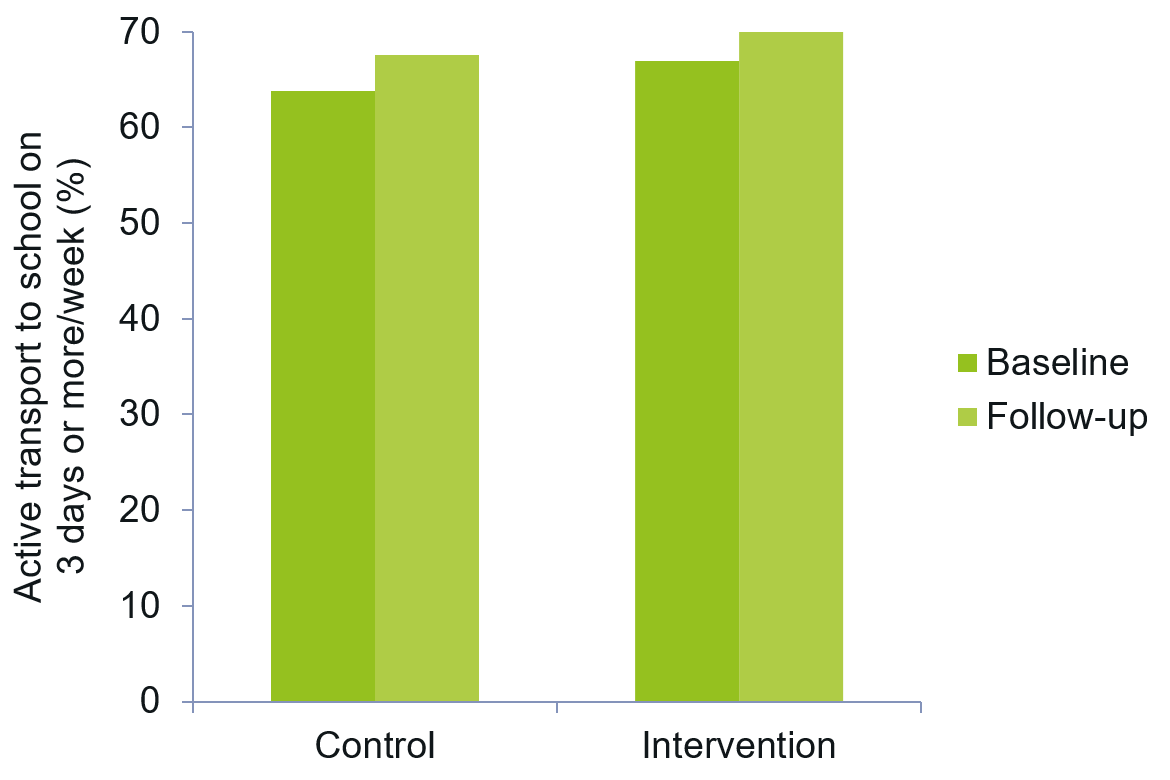

Physical activity

Assessed subjectively, at baseline, children engaged in 60 minutes of moderate-to-vigorous physical activity (MVPA) on 2.74 (± 1.66) days per week. 31.9% and 22.2% of boys and girls, respectively, spent at least four days per week being moderately to vigorously physically active for at least 60 minutes. At follow-up, boys spent marginally more time in MVPA and there was a tendency towards more physical activity in the intervention group and a slight, although not statistically significant, reduction of physical activity in the control group (Kobel et al., 2014).

Physical activity was also assessed objectively. At follow-up, significant effects were found for MVPA and gender as well as MVPA and weight status, with boys being more active than girls and overweight/obese children being more active than normal weight children (T -5.646 p < 0.01; T -3.998 p < 0.01, respectively)͘. Further, more children in the intervention group reached the recommended activity guidelines of 60 minutes daily in MVPA; yet no significant significance was reached (Kobel et al., 2017b).

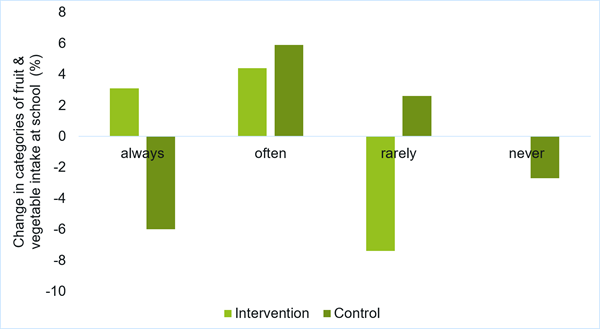

Fruit and vegetable intake

Fruit and vegetable intake increased significantly for first graders (p = 0.050), children from families with high parental education levels (p = 0.023), and children with overweight fathers (p = 0.034). Significant group differences were found in the fruit and vegetable intake of children with migration backgrounds (p = 0.01) and those with parents who have a high school degree (p = 0.019) (Kobel et al., 2022a). When controlling for migration background, the proportion of children in the intervention group who never or rarely ate fruit and vegetables decreased significantly from baseline to follow-up (p = 0.010) (Kobel et al., 2017c).

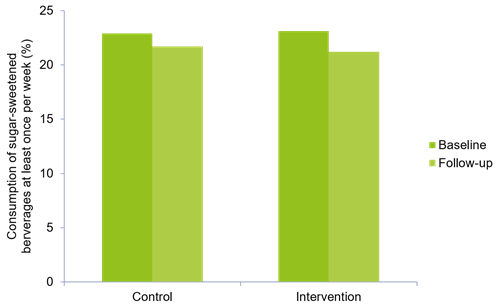

Sugar-sweetened beverage consumption

At baseline, 24.6% of boys and 22.6% of girls drank sugar-sweetened beverages at least once per week. A significant reduction of soft drink consumption was seen in both the intervention and control group, with trends in a greater reduction among the intervention group (Kobel et al., 2014).

Among children with migration backgrounds, there was a significant decrease in their parental reported regular pure juice consumption from baseline to follow-up (29% to 20.2%; p = 0.004.) Children from households with low incomes also saw a reduction of pure juice consumption (32.9% at baseline – 22.4% at follow-up; p = 0.012) (Kobel et al., 2022a).

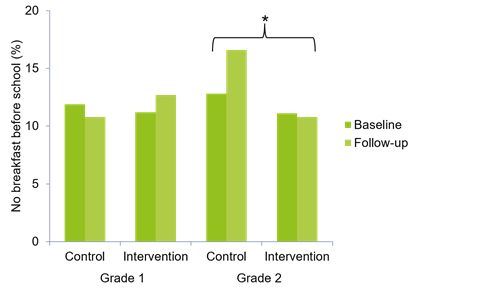

Skipping breakfast

At baseline, 12.9% of children reported that they rarely eat breakfast before leaving for school. At follow-up, a tendency could be observed of children in the control group skipping breakfast more often, whereas the number of children who skipped breakfast in the intervention group remained the same. Considering children in grade one and grade two separately, this trend becomes significant among second graders: the second graders in the control group skipped breakfast significantly more often than those in the intervention group (OR = 0.52, p = 0.024, 95% CI [0.30;0.92]) (Kobel et al., 2014).

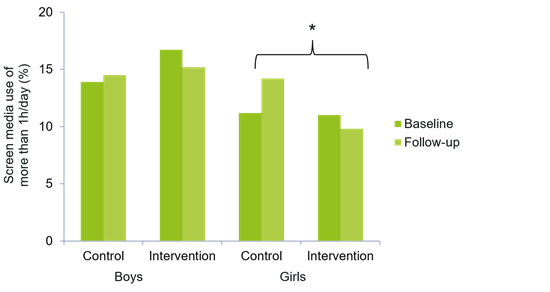

Screen media use

Baseline results of screen media use show that 15.4% and 11.2% of boys and girls, respectively, spent a minimum of one hour per day using screen media. At follow-up, there was a tendency towards less screen media use in the intervention group, whereas the opposite trend could be observed in the control group. Considering girls and boys separately, there is a significant difference between control and intervention groups with only girls in the intervention group using significantly less screen media per day than their counterparts in the control group (OR = 0.58, p = 0.04, 95% CI [0.35;0.96]).

Significant positive intervention effects on screen media use have been found in children (boys and girls) without a migration background as well as in children whose parents have a low education level (OR = 0.61, p = 0.043, 95% CI [0.38; 0.98] and OR = 0.64, p = 0.032, 95% CI [0.43; 0.96], resp.) (Kobel et al., 2014).

Sedentary time

Objectively assessed, at baseline, children spent 211 (± 89) minutes daily being sedentary, at follow-up 259 (± 109) min/day with no significant difference between the intervention and control group. Sedentary behaviour was higher during weekends (p < 0.01, for control and intervention group). At follow-up, daily screen time decreased in IG (screen time of >1 h/day: baseline: 33.3% vs. 27.4%; follow-up: 41.2% vs. 27.5%, for CG and IG, respectively) but not sedentary time (Kobel et al., 2020a).

Sick days and school absence

Significant differences occurred in the number of days children missed at school because of sickness and in the number of maternal days off work in favour of the intervention group. Children in the intervention group had a significantly higher reduction in sick days. This effect remains stable for children in grade 1 after adjustment for gender, migration and baseline values for sick days. First grade children in the intervention and control group had a change of −5.15 vs. -3.64, respectively, in the numbers of sick days between baseline and follow up, indicating a group difference of 1.51 days (p = 0.02). ICC for the differences in sick days was 0.045 (95% CI [0.012;0.078]) (Kesztyüs et al., 2016)

Children who adhered to physical activity guidelines had significantly less days of absence due to illness than children who did not meet physical activity guidelines (p < 0.001) (Kobel et al., 2022b).

Economic aspects and costs of the programme

The costs for two seminars for the consulting teachers added up to €2164.48, with the highest amount of money spent on the teachers´ accommodation, travel and catering. The three vocational training sessions added up to €5872.00, the distributed folders for all teachers, advertising materials and the catering were the most expensive positions. The personnel costs contained costs for consulting teachers and the staff of the university and were, in total, the highest position at €28469.93. The total amount of the intervention for one year was €36506.41, which resulted in an intervention cost of €25.04 per pupil (Kesztyüs et al., 2017).

The incremental cost-effectiveness ratios, in this scenario the costs per case of incidental abdominal obesity averted, varied between €1515 and €1993, depending on the size of the observed target group. Hypothetical changes in the effect of the intervention on the incidence rate of ± 10% and ± 20% respectively, resulted in a minimum of costs per case averted of €1789.53 and a maximum of €1963.92 (Kesztyüs et al., 2017).